Ernst Pagels – Dedicated to Perennials

It is a lucky person who finds there calling in life, and is able to spend a fulfilling and satisfying life doing what they love. Although his name is not widely-known, Ernst Pagels certainly achieved that. He turned an unpromising beginning into a creative and successful life, during years of political turmoil and war. In doing that he left gardeners a legacy of perennial flowers they are still growing today, especially among ornamental grasses.

The role of Germany in creating the modern perennial garden is often overlooked among English speakers, but it is far more significant than many today realize. Three names stand out. First is the pioneer breeder Georg Arends, today remembered mostly for his Astilbe, many of which are still grown, although bred in the very early 20th century. Second is Karl Foerster, who we have already written about, and whose impact on design as well as in plant breeding can hardly be overstated. Third in line is Foerster’s most important protégé, Ernst Pagels.

Uncertain Beginnings

Pagels came from a humble background, and didn’t have the opportunity to attend prestigious gardening schools. He was born as the storm-clouds of World War I were gathering, in 1913, to parents who had a plant nursery. His father died in the first year of the war, and his mother was overwhelmed raising children and running a business, so she sent Ernst to live with his paternal grandparents. His life with them was idyllic, but it came to abrupt end at 10 when his grandmother died and he was sent back to his mother in the town of Leer, in East Friesland (Lower Saxony), close to the Dutch border. He hated his life there, and resisted his family’s wishes that he train as a teacher.

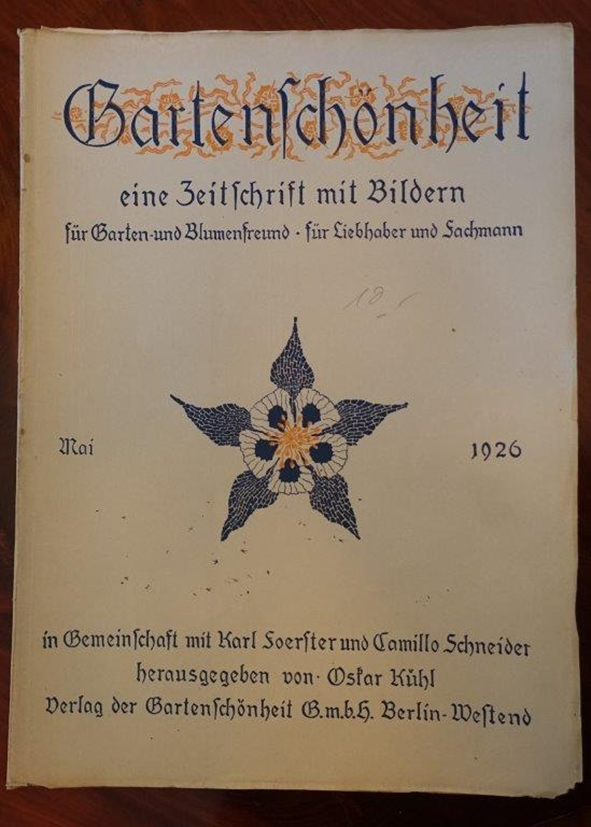

Instead, at 18 he apprenticed at the local van Scharrel nursery. While working there he came across a magazine called Gartenshonheit (Garden Beauty), published by Karl Foerster, who was already a major figure in German gardening, and a pioneer in breeding and designing with perennials. Pagels become fascinated, and would sneak away from his work to the attics, and pore over copies of this magazine. By luck and hard work he had the opportunity to work on the installation of a garden by Foerster, and from then on he was dedicated to perennials, and to Foerster.

After six months at van Scharrel he moved east to a school in Oranienburg, qualify as a horticultural technician after two years. He spent the next years working in Germany, Switzerland and Italy, and developing an early interest in the biodynamic horticulture of Rudolf Steiner. In 1937 his dream of working with Foerster came true when he found a job at Foerster’s nursery and garden in Bornmin, near Potsdam. He began packing plants for shipment and worked his way up to become a manager. His greatest pleasure, and education, during these years was evening walks with Foerster around the gardens, discussing breeding and gardening. Change struck again all too soon, and in 1939 he was called up, fighting for the German army in World War II.

At some point in the war he was captured by the British, and was a POW when the war ended. It took some time before he was released, returning to Leer. Life in post-war Germany was hard, but his mother’s parents had 5 acres of land. He wasn’t able to set up the nursery he wanted to because regulations required land to be used for food, so he did that, waiting for things to improve. In 1949 he finally received permission to set up his perennial nursery.

Flattened by the relentless bombing of the war, Germany needed almost complete rebuilding. As wealth returned architects had plenty of work, and Pagels had a stroke of luck when Carl Börner, an architect he had met while working for Foerster moved to Leer. It was natural that Börner would ask Pagels to design and build the gardens of the homes he created, but Pagels didn’t have the design skills. A second stroke of luck helped him out. A top designer from Foerster’s pre-war team was an internal refugee, living nearby, and Pagels offered him a job. They become close associates for many years, and both Börner and Pagels thrived on the highly-praised private and public projects they built.

Pagels built an extensive network around the world with other perennial growers. His contacts included England’s Beth Chatto and the Dutch designers Mien Ruys and Piet Oudolf, who created the ‘next wave’ of perennial gardening, the New Perennial Movement. In the 1960s his nephew Enno Winenga began to take over the design work, so that by the mid-70s he was able to devote his time entirely to breeding. After 2000 Pagels stepped aside – he was almost 90 by then. When Pagels died in 2007 he left his nursery to the Steiner movement, who turned it into a public garden and Waldorf School. Today the gardens are run by a non-profit ‘Friends of the Garden’, to preserve his legacy of plants and keep the gardens open to everyone, as a place of learning.

Pagels’ Legacy of Perennial Plants

When you sow a packet of seeds you expect the seedlings to all be the same. You might be surprised to discover that breeders have to work hard to achieve that. Nature is much more interested in variation, and wild seeds are very variable, not at all the same. It’s nature lottery –let’s try all these different combinations and see which ones succeed. That approach, which Foerster also used, was adopted by Pagels, who always said he wasn’t a plant breeder but simply a selector. This involved planting a large number of seedlings and then seeing which had interesting colors or habits, which were both sturdy and attractive, or whatever trait was desired.

Pagels had started in 1949 with Delphiniums, but his first big achievement began with a gift from Foerster of a packet of seeds of the wood sage, Salvia nemerosa. We can presume it was a large packet – Foerster used between 20 and 30,000 seedlings for his selection. He said to Pagels, “There are three good plants in this packet – find them.” Since Foerster grew many different species in his gardens, it is likely that at least some of the seeds were hybrids – the plant we call today Salvia x sylvestris, the wood sage – but we don’t know for sure. Following the suggestion, Pagels did indeed name just 3 varieties in the batch. The most famous and enduring he released in 1955, with the name ‘Oestfriesland’ – the East Friesland Sage. The winner of multiple awards, this plant is still widely planted and among the most desirable of the flowering sages.

After that first success many more followed, with Pagels selecting 13 more new sages, 8 new yarrows (Achillea), 8 Sedum, 7 Rodgersia, and new varieties of numerous other perennials during his lifetime. He ended up with 10 award-winning plants from BdS, the Association of German Perennial Gardeners, and won multiple prizes and honors right up to his death. He always selected plants that were beautiful, vigorous, reliable, and that look good for as long as possible – principles he learned from Foerster.

In the 1980s he shifted his attention to grasses, especially Maiden Grass, Miscanthus, one of the largest and most beautiful of all grasses. His work added significantly to bringing grasses to the prominent position in gardens they have today. In Germany Miscanthus blooms late, and rarely produces viable seed. So Pagels had to move into the greenhouse, mastering the art of breeding them in an artificial environment. He created numerous new varieties from the common ‘Gracillimus’, especially smaller varieties for smaller gardens.

In 2001 Britain’s Royal Horticultural Society ran trials on Miscanthus varieties, and of the 16 given the prestigious Award of Garden Merit, half of them were raised by Pagels. These included ‘Flamingo’, ‘Kleine Silberspinne’, ‘Kleine Fontäne’, and ‘Septemberrot’. All this when he was already in his 80s. A long and productive life indeed.